Forensic analysts are highly specialized professionals who play a crucial role in investigating and analyzing evidence in criminal cases. They employ scientific techniques to examine a wide range of materials, from DNA and fingerprints to digital data and firearms, to provide valuable insights and assist in the prosecution of criminals.

Responsibilities of a Forensic Analyst

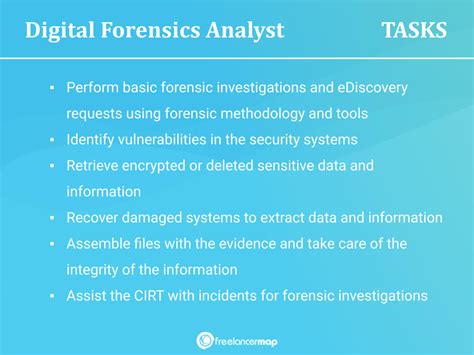

The responsibilities of a forensic analyst vary depending on their area of specialization, but their primary duty is to:

-

Collect and Analyze Evidence: They collect and preserve evidence from crime scenes, using proper methods and techniques to ensure its integrity. They analyze evidence to identify and interpret potential connections to the crime or suspect.

-

Interpret Findings: After examining the evidence, forensic analysts interpret their findings to determine the significance of the evidence and its relevance to the case. They may also provide expert testimony in court to explain their analysis and present their conclusions.

-

Prepare Reports: They document their findings in detailed reports, which include descriptions of the evidence, analytical methods used, and their conclusions. These reports serve as vital documentation for investigators, prosecutors, and defense attorneys.

Types of Forensic Analysis

Forensic analysis encompasses a wide range of specializations, including:

- DNA Analysis: Isolating and analyzing DNA from evidence to identify individuals involved in a crime, such as suspects, victims, or witnesses.

- Fingerprint Analysis: Examining and comparing fingerprints found at a crime scene to identify individuals or exclude suspects.

- Ballistics Analysis: Analyzing firearms, ammunition, and bullet markings to determine the type of weapon used, reconstruct shooting events, and compare evidence to other crimes.

- Document Analysis: Examining handwritten or printed documents to verify authenticity, identify forgeries, or determine the authorship of anonymous letters.

- Digital Forensics: Recovering and analyzing electronic data from computers, phones, and other devices to identify evidence of crimes, such as cyberattacks, fraud, or child exploitation.

Education and Training

Forensic analysts typically hold a bachelor’s or master’s degree in forensic science, criminal justice, or a related field. They may also receive specialized training in their area of focus, such as DNA analysis or ballistics. Many forensic analysts gain experience through internships and on-the-job training before becoming certified by professional organizations.

Job Outlook

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the job outlook for forensic science technicians, including forensic analysts, is projected to grow by 17% from 2020 to 2030, faster than the average for all occupations. This growth is expected to be driven by the increasing use of forensic science in criminal investigations.

Challenges and Rewards

Challenges:

- Dealing with sensitive and potentially disturbing evidence

- Working on high-stakes cases with limited time and resources

- Maintaining objectivity and professionalism in emotionally charged situations

Rewards:

- Contributing to the pursuit of justice and protecting society

- Using scientific knowledge and skills to solve complex problems

- Making a real difference in the outcome of criminal cases

Applications of Forensic Analysis

Forensic analysis has numerous applications beyond criminal investigations, such as:

- Historical Analysis: Examining artifacts and documents to uncover historical facts and events.

- Art Authentication: Determining the authenticity of paintings, sculptures, and other works of art.

- Environmental Analysis: Analyzing pollutants and contaminants to identify their sources and assess their impact on ecosystems.

- Product Safety Analysis: Examining products to determine their safety and compliance with regulations.

- Forensic Genealogy: Using DNA analysis to trace ancestry and identify unknown individuals in historical or adoption cases.

Useful Tables

| Table 1: Types of Forensic Analysis | Methods Used |

|---|---|

| DNA Analysis | Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), DNA sequencing |

| Fingerprint Analysis | Comparison of ridge patterns, chemical enhancement |

| Ballistics Analysis | Microscopic examination, ballistic testing |

| Document Analysis | Ink analysis, paper examination, handwriting comparison |

| Digital Forensics | Data recovery, file analysis, network investigation |

| Table 2: Education and Training Requirements for Forensic Analysts |

| Degree | Specialization | Certification |

|—|—|—|

| Bachelor’s Degree | Forensic Science, Criminal Justice, Natural Science | Certified Forensic Science Technician (CFST) |

| Master’s Degree | Specific Forensic Science Discipline | Board-Certified Forensic Analyst (BCFA) |

| Training | On-the-Job Training, Internships | Specialty Certifications (e.g., DNA Analyst, Ballistics Expert) |

| Table 3: Job Outlook for Forensic Analysts |

| Year | Projected Growth |

|—|—|

| 2020 | Baseline |

| 2030 | 17% |

| Table 4: Applications of Forensic Analysis Beyond Criminal Investigations |

| Area of Application | Purpose |

|—|—|

| Historical Analysis | Uncovering historical truths |

| Art Authentication | Verifying authenticity of artworks |

| Environmental Analysis | Identifying pollution sources and environmental impact |

| Product Safety Analysis | Ensuring product safety and compliance |

| Forensic Genealogy | Tracing ancestry and identifying unknown individuals |