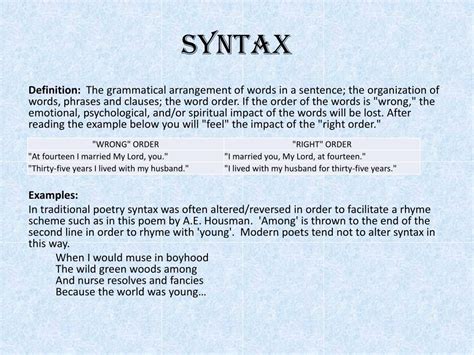

Syntax, the arrangement of words and phrases to create meaning in a sentence, is a crucial element of literary expression. In poetry, syntax becomes a powerful tool for conveying emotions, evoking imagery, and shaping the reader’s experience. This article explores the various ways in which poets manipulate syntax to achieve their desired effects.

Inversion for Impact

Inversion, reversing the expected word order, is a common technique employed by poets to emphasize certain words or phrases. By departing from the conventional subject-verb-object pattern, poets can highlight specific elements and create a sense of intrigue or surprise.

-

Example:

“The world is too much with us; late and soon, / Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers” (William Wordsworth, “The World Is Too Much with Us”)

Enjambment for Continuity

Enjambment, running a sentence or clause over multiple lines, allows poets to break the flow of thought and create a sense of continuity or suspension. This technique helps establish a rhythm and build anticipation within the poem.

-

Example:

“A silver-throated loon / Whose wail follows / The evening star” (John Masefield, “Sea Fever”)

Parallelism for Emphasis

Parallelism, arranging similar grammatical structures in sequence, creates a sense of balance and parallelism. Poets use this technique to emphasize ideas, draw comparisons, or create a lyrical effect.

-

Example:

“I shall be telling this with a sigh / Somewhere ages and ages hence: / Two roads diverged in a yellow wood” (Robert Frost, “The Road Not Taken”)

Anaphora for Repetition

Anaphora, repeating words or phrases at the beginning of successive lines, helps create a sense of rhythm and build momentum in the poem. Poets use this technique to reinforce an idea or evoke a specific emotion.

-

Example:

“And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain / Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before” (Edgar Allan Poe, “The Raven”)

Hypotaxis for Complexity

Hypotaxis, using a series of subordinate clauses, creates a complex and hierarchical structure. Poets use this technique to develop an idea gradually, building tension and suspense within the poem.

-

Example:

“When I have fears that I may cease to be / Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain, / Before high-piled books, in charactery, / Hold like rich garners the full ripen’d grain” (John Keats, “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be”)

Tips for Using Syntax in Poetry

- Experiment with different word orders. Varying the position of words and phrases can create different shades of meaning or emphasis.

- Use enjambment sparingly. While enjambment can enhance a poem’s flow, excessive use can make it difficult for readers to follow the thought.

- Balance parallelism. Avoid using too many parallel structures in succession, as it can make the poem monotonous.

- Consider anaphora’s impact. While anaphora can create repetition, it can also become predictable if overused.

- Choose syntax that supports the poem’s theme. The syntax should work in harmony with the poem’s overall content and mood.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Inversion for the sake of it. Do not invert word order solely for the purpose of creating an effect. Ensure that the inversion serves a specific poetic purpose.

- Excessive enjambment. Overusing enjambment can disrupt the flow of thought and make it difficult for readers to understand the poem’s structure.

- Repetitive parallelism. Avoid creating a series of parallel structures that simply restate the same idea.

- Unclear anaphora. Ensure that the repeated words or phrases in anaphora are clear and meaningful.

- Ill-fitting syntax. Do not force syntax into a mold that does not suit the poem’s content or tone.

Conclusion

Syntax is a vital element of poetry, allowing poets to convey meaning, evoke emotions, and shape the reader’s experience. By understanding and utilizing the various syntactic techniques, poets can create powerful and evocative works that resonate with readers.